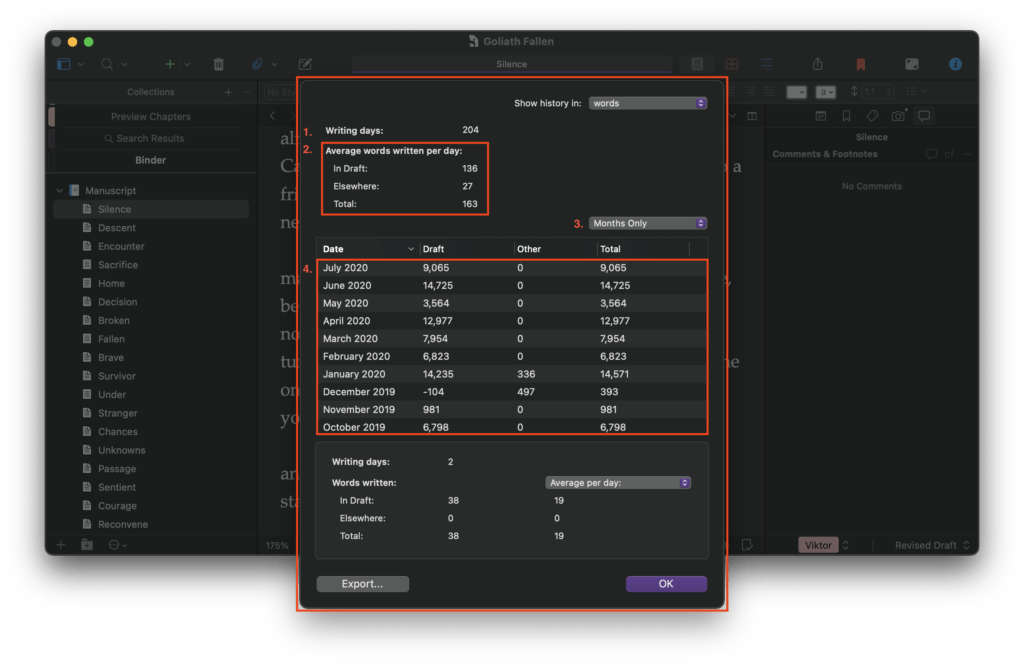

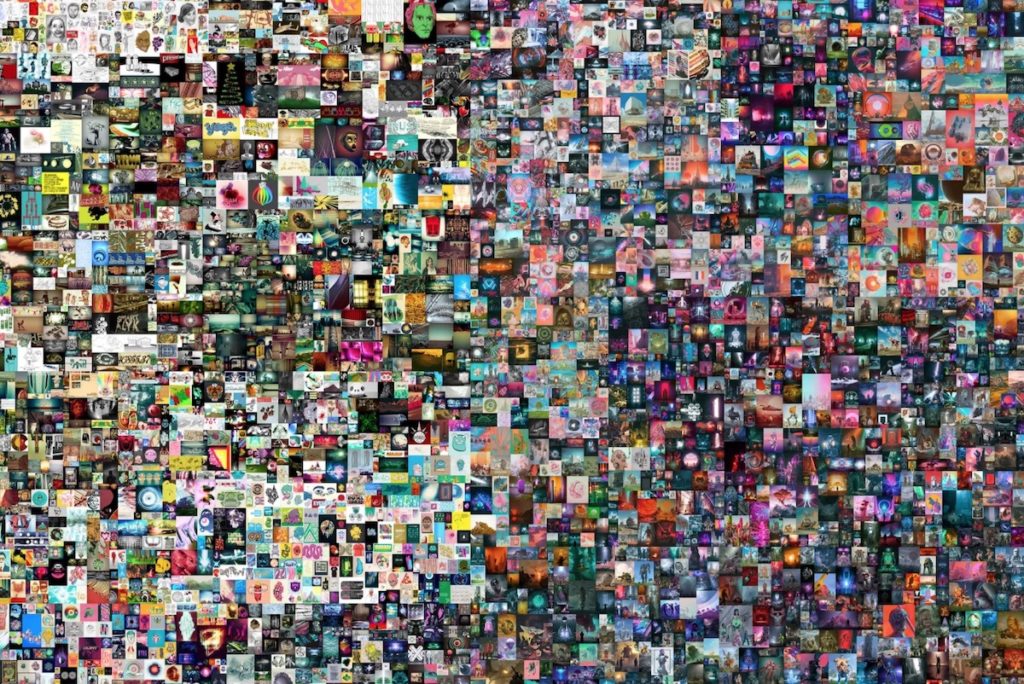

If you’ve spent more than 30 minutes on the internet lately, you’ve probably already heard about NFTs. Stories abound of artists auctioning JPEGs for millions of dollars in the ever-growing community of crypto enthusiasts. South Carolina-based artist Beeple famously sold his EVERYDAYS: THE FIRST 5000 DAYS piece (a collage of 5,000 digital images from his collection of the same name) for $69 million at Christie’s, a sum so mind-boggling that it earned a rightful place in newspaper headlines around the world. And, for all that cash, buyer Vignesh Sundaresan got to call dibs on an image anybody can just download online.

If you’re confused, you have every right to be. I’m a software engineer in my early 30s, and I’ve never felt so close to what my dad must’ve experienced back in the 90s when he first heard about “the internet”. Even if it seems like technology is heading into bizarre places, we, as authors, can’t afford to fall behind. We shouldn’t let the magic computer box intimidate us. Instead, we can open our minds, learn more about these insane trends, and make them work in our favor.

So, we arrive at the question we’re here to answer: what are NFTs, and how can authors leverage this technological madness to take our work to the next level?

The initial NFT craze left me lost and clueless at first. But, after some in-depth research, I was able to descend the steep learning curve to truly understand NFTs, their value, and how they can become the next great art form. Armed with this new knowledge, I decided to write this article to help you navigate these strange waters and avoid the same perils I did.

The fundamentals

To use NFTs in our favor, it’s necessary to understand a few fundamentals first. If you’re already somewhat knowledgeable about cryptocurrency and the blockchain, this might feel repetitive. Feel free to skip this bit—it’s not like it took a lot of work to put together and my heart will break into a million pieces or anything (spoiler: it will).

What are NFTs?

NFT stands for non-fungible token. In plain English, an NFT is something unique and non-reproducible. For illustrative purposes, let’s say you have a dog. You’ve spent years together, and it has become your entire world. Unfortunately, nothing lasts forever. One fateful day, your dog passes away. You hurt and grieve, and, after a few years go by, you finally bring yourself to get another one. But, despite how great this new dog is, it will never fill the void your old friend left in your soul. That’s because your first dog is non-fungible—there was no other one like it and there never will be. It cannot be replaced.

Some folks explain NFTs using an example of the Mona Lisa and how although we can make copies of it, they’ll never be the same as the original. It’s a good example, but I thought something more personal would help you better grasp the concept. Sorry if I made you sad.

So, we now know that something that is non-fungible cannot be replicated. But, what does token mean in this context? A token is simply a representation of something.

Therefore, when put together, a non-fungible token is a representation of something unique and non-reproducible. We can also see it as a title of ownership over a collectible. Going back to the Mona Lisa example, buying the NFT is like buying the title deed of the original work. It’s ours now. We might as well walk into the Louvre, grab the painting under our arm, and ride the bus back home. The same goes for Beeple’s EVERYDAYS: THE FIRST 5000 DAYS. The buyer didn’t pay $69 million for a JPEG; he paid for the title of ownership over the original art. He’s now free to sell it whenever and to whomever he pleases (and probably for a far higher price).

But, if we’ve had titles for ages, how are NFTs different?

The answer is decentralization and immutability. NFTs are stored in a special public database called the blockchain. We’ll dive deeper into that next, but, long story short, nobody (human or machine) can tamper with the data stored in the blockchain. While titles can be forged and people tricked into buying something they think is original, every transaction associated with NFTs is public. Anybody can see who was the original author and who currently owns it. If that owner isn’t us, we’ll only make a fool out of ourselves trying to sell that forgery.

What is the blockchain?

The blockchain is a concept often associated with cryptocurrencies (e.g., Bitcoin). In simple English, the blockchain is just a type of database. For example, the transactions that determine the balance of your savings account are stored in a database owned by your bank. They have complete access to that data and can do whatever they want with it; it’s owned by a single entity. Although unlikely, what happens if a hacker gets access to it? They could make drastic, irrevocable changes. Such centralized databases are vulnerable if they’re not properly secured.

On the other hand, the blockchain is a distributed database. Thousands of computers worldwide hold a copy of the entire data. To change that data, all of those computers need to agree. If someone attempts to tamper with the data in one location, it’ll be blocked as the majority won’t agree with the change. That hacker will then be flagged as a dirty cheater and banned from ever participating in the blockchain again.

The blockchain stores the NFTs and their entire history, including who originally created it, who has owned it, and who the current owner is. And not only that, but all the information is public and can be verified by anyone. All this is to say that the data in the blockchain is immutable and incorruptible.

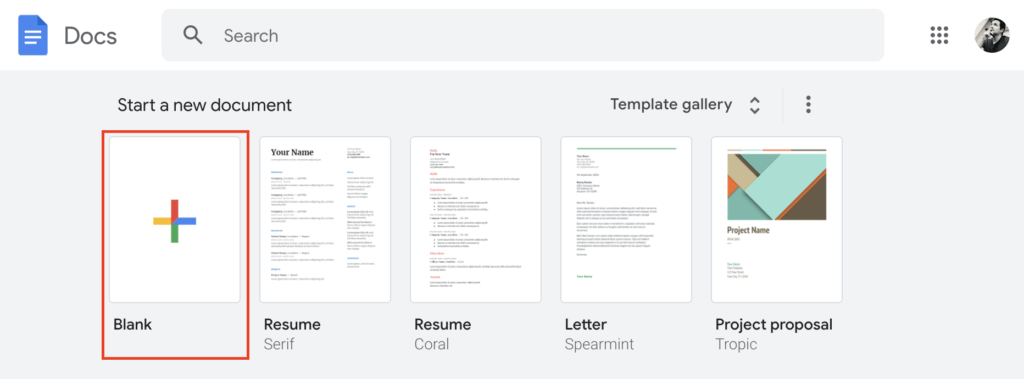

How are NFTs made?

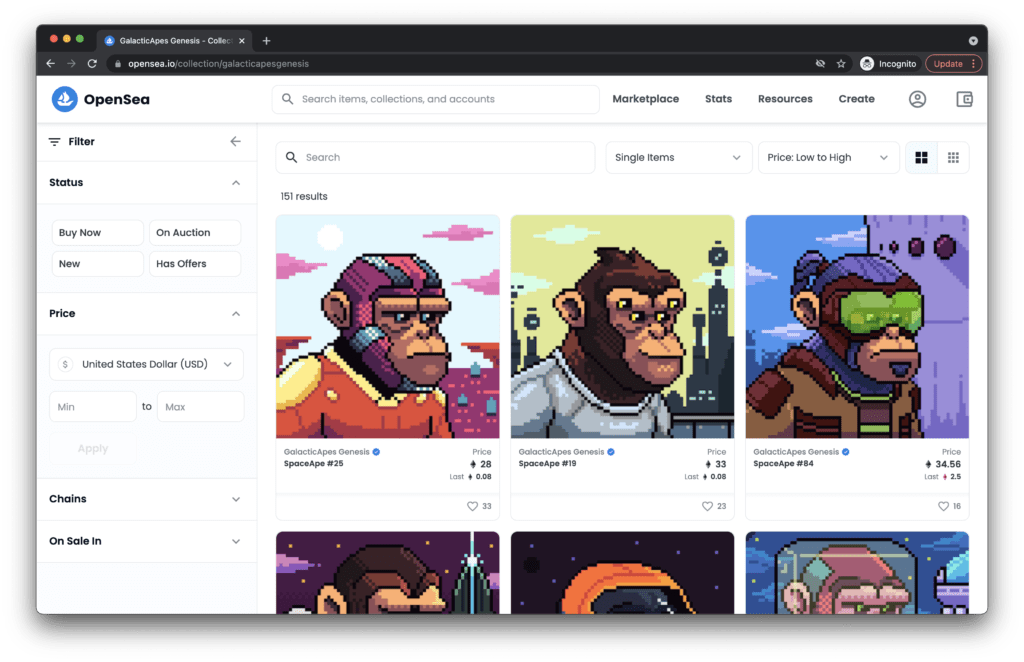

There are several ways to create NFTs, but the easiest is through an NFT marketplace. There, we can easily “mint” (“create”), auction, sell, transfer, and buy NFTs as well as NFT collections. One of the most popular marketplaces is OpenSea, which, by the way, carries Beeple’s EVERYDAYS collection.

It’s essential to remember that marketplaces are just storefronts to the blockchain that stores the NFTs. All marketplaces share the same database. While OpenSea lists Beeple’s collections, it doesn’t mean that they’re only available there. Nifty Gateway, another popular marketplace, also lists his pieces.

How do artists use NFTs?

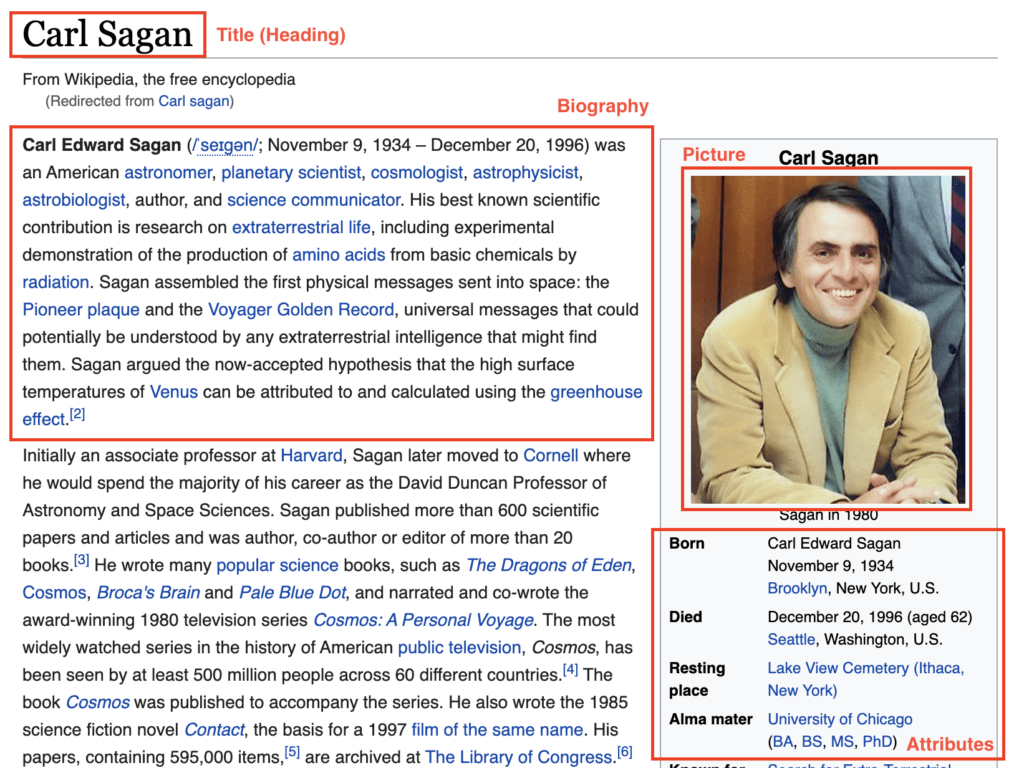

As you may have noticed, NFTs are commonly associated with visual art. Marketplaces let artists associate their freshly minted NFTs to the original asset (a high-resolution image or video) and a set of attributes. Digital collectibles such as cards are a common type of collection where an image of a character is uniquely replicated with varying attributes (including hair color and style, age, gender, etc.). This can give a specific NFT rarity. For example, only one character in the collection has hazel eyes. Famous collections include Doodles, CryptoPunks, and GalacticApes.

Other collections, such as Beeple’s, are closer to something like pieces in a museum. Interestingly enough, some art collectors “convert” physical art pieces into an NFT by destroying the original work. One of the most prominent cases was the burning of an original work by Banksy, which now lives forever in the blockchain as a digitized version.

Cryptocurrency

NFT marketplaces don’t use traditional currencies (like the dollar) because the blockchain has its own money. The most popular (and original) blockchain for NFTs is Ethereum. To transact on Ethereum, we’ll have to get ourselves some Ether, its native digital currency. Just like how we need to use local currency to buy things in a foreign country, we’ll need to do the same for each blockchain.

But, where can we exchange dollars for Ether? And, more importantly, if we sell an NFT and get paid in Ether, how can we get dollars back in order to buy things in the “real world”? Without delving too far into the details of buying and selling cryptocurrency, you can simply sell your Ether through a crypto exchange like Coinbase. It’s the same as exchanging dollars for euros, for example.

How can authors use NFTs?

Now that we have the basics of NFTs down, it’s time to discuss how to put them to work in the literary world. While there are countless collections of visual art in NFT marketplaces, literary NFT projects are a little more scarce as of now. Writer Anand Giridharadas is an example of an early pioneer with his Winners Take All collection. As the description declares, it’s “an experiment in applying NFTs to the literary world”. This is a crucial point: adapting the NFT medium to literature takes a good amount of experimentation and creativity.

Other creative projects in this space include The Chaintale by Italian artist Brickwall, which lets the buyer of his latest NFT write the next installment in the series like an interactive game. It might sound complex and involved. However, if I’ve learned anything, it’s that the crypto community is very much into the intricate and sophisticated. If anything, it makes the project that much more unique and valuable.

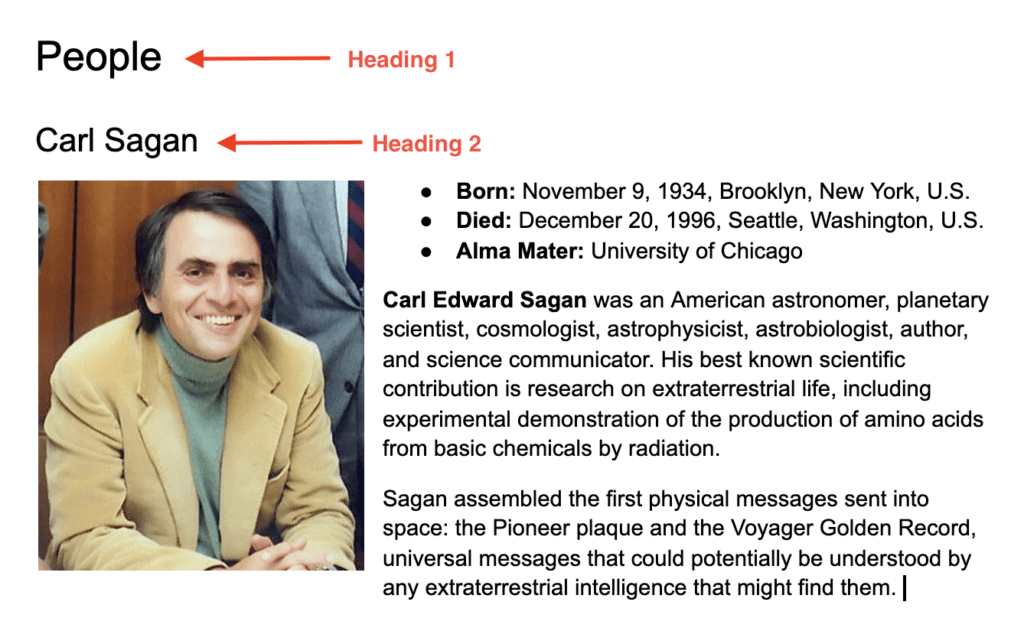

There are several ways authors can make their entrance into the NFT space, from creating a limited run of our latest book to turning central passages into an image or developing trading cards of primary characters. Some pursuits are easier than others, but, as I mentioned earlier, the NFT space is mainly a visual one, so visual content is preferred. In the end, it’s the same as creating merch for our works.

Before moving on, let’s always remember this golden rule: only publish something that we would see ourselves wanting and paying for. We wouldn’t pay for a cheap GIF that offers no real value, would we? Look to develop something unique and special that your audience will get excited about. After all, for authors, expanding our reach into NFTs isn’t just about making money; it allows us to engage with existing readers in a new fashion. It also lets us reach an untapped audience for our work. A little bit of effort can go a long way.

The first copy of our book

There’s only one first copy. To me, that sounds like the perfect use case for an NFT. For our next book, we can consider creating an NFT giving the buyer ownership of the very first digital copy. We can preferably customize that copy to make it as unique as possible, like using a special cover (with custom art, different layout, letter coloring, etc.), a signed cover, a personalized thanks in the intro, or any other extra content to make it special.

Some companies also offer services to create physical NFTs, meaning that the first copy could be an actual, physical hard copy. In that case, we can try out more ideas like a special hardcover. What would we like to see from a truly unique first copy if we were one of our readers?

A limited run of our book

In addition to a unique, super special first copy of our book, we can also make a limited run of the same—a special edition, if you will. Our audience might not see it as something as special as a first copy, but it will be more accessible to a broader part of our audience. Again, we should primarily strive to bring our readers value rather than money into our pockets; usually, the former results in the latter anyway.

For limited runs, we can create a separate, numbered NFT per copy and list it on the marketplace. There must be something special about those copies though. For example, we can consider making a different version of the cover featuring the run number, the name of the limited edition (if any), and a special note inside. What would make you want one of those copies as a reader?

Short stories with a hidden storyline

We can really go the extra mile by creating short stories that exist as separate branches off of the main storylines of our novels. To make the NFT as visual as possible, we can offer custom cover art in addition to the PDF file of the story. The more unique the story, the better. Also, consider throwing in special thanks and other goodies to make the owner feel like they’re holding something one of a kind and unforgettable.

Collectibles related to our book’s lore

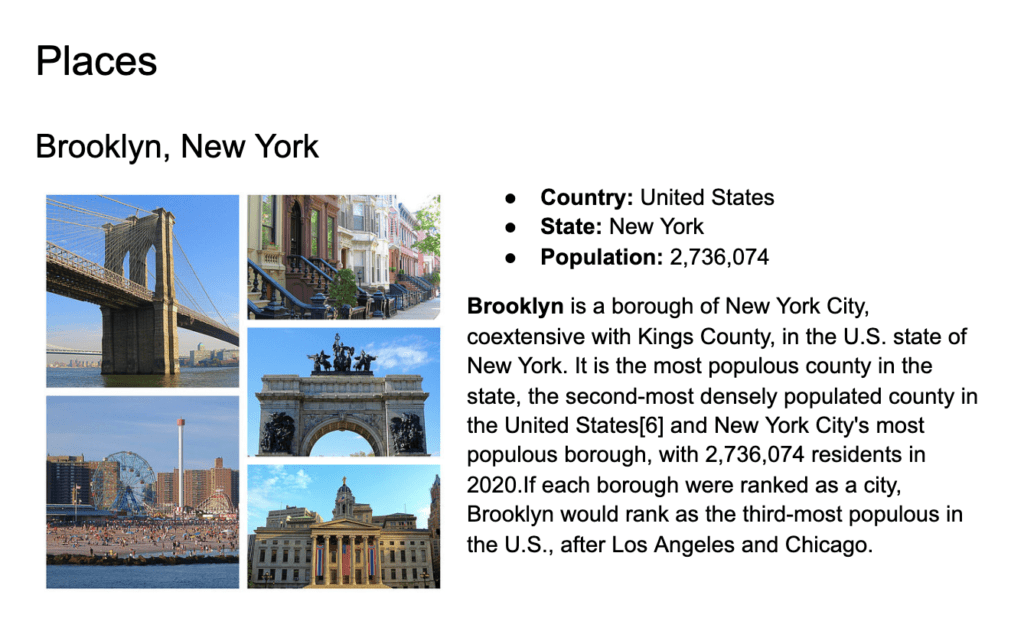

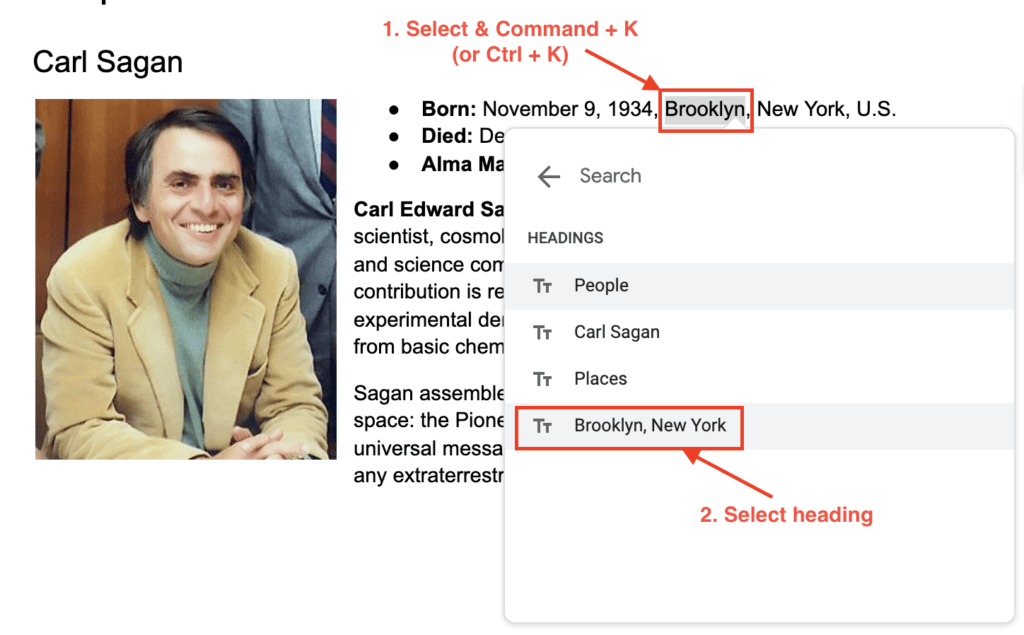

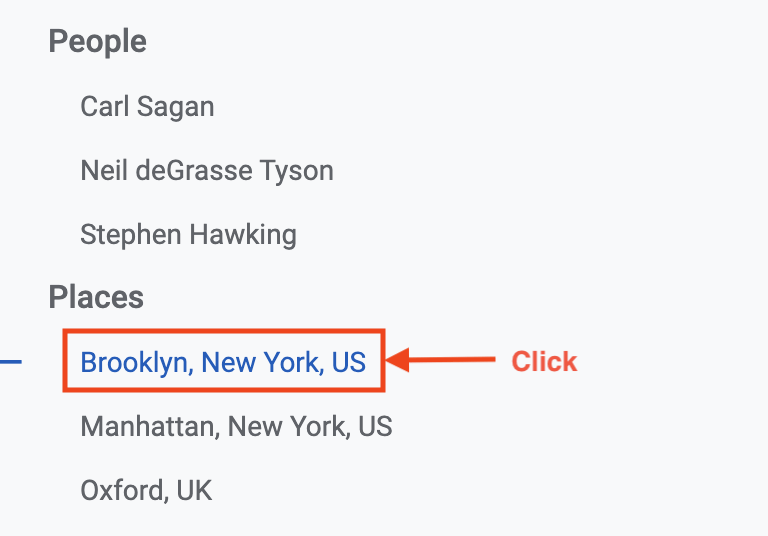

As mentioned before, if we can create physical merch for our books, then it’s possible to create NFTs as well. For example, we already have an idea of what our characters look like and their attributes. We can now leverage that to mint a collection of our characters in the form of collectible cards. If we’re writing fantasy, sci-fi, or other stories with rich lore, we can also have cards of artifacts, locations, magic, etc.

This might require working with an artist or someone who can produce professional-quality images worthy of an NFT. It doesn’t have to be super expensive either. Some artists may be even willing to consider taking a cut of the NFT’s sales—many comic book projects work under this model. Even if we end up paying for design services upfront, if we’ve come up with something truly unique, there’s a strong possibility we’ll make our money back (and then some).

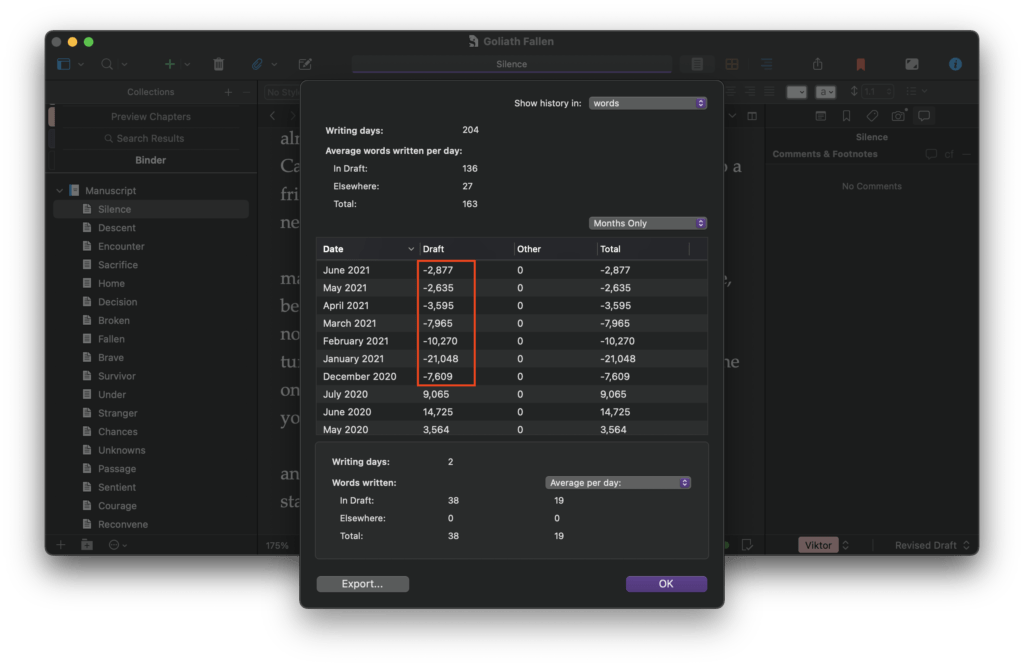

Never-before-seen, unedited material

Last but not least, we have the good ol’ exclusive, unedited material. This can include early versions of our drafts, previews of our cover art, deleted characters or other story elements, and much more. That file sitting in the desktop recycle bin might offer our most loyal fans an exclusive look into our process. Consider just how valuable that manuscript someone found tucked away in J.R.R Tolkien’s drawer is today.

I’ve talked with some of my readers, and, when I mention early versions of my book covers, they find them interesting and valuable. As the author, it’s sometimes hard to conceptualize what’s best suited for an NFT. If we’re struggling to come up with ideas, we can always ask our audience what they would like to see released.

Final thoughts

In summary, NFTs represent items that are unique and valuable. They provide a new, powerful medium of distribution for our literary work in a truly exclusive, premium, and personal fashion to our loyal reader base. If we can create merch for our books, we can also create NFTs.

In order to catch on, however, they should be our most valuable and exclusive goodies. We always have to strive for value and think of what we would like to see (and purchase) as a reader. If we wouldn’t buy it ourselves, it’s likely our readers won’t either. Literary NFTs are still very new, but there’s plenty of potential for us authors to take our work to the next level. Now’s the time to experiment and explore this new form of media.

In this article, we discussed what NFTs are and how authors can put them to work for their own benefit. As the NFT space continues to evolve, there will be ample opportunity to take advantage of new blockchain projects; we’ve really only scratched the surface in terms of the value of NFTs and digitization.

I hope this has helped reframe your thinking of what’s possible when promoting your written work and engaging with your audience. Let me know if you’d like to see a deeper dive into NFTs and other crypto topics for writers. Perhaps this can become a new series.

Did you already know about NFTs? Have you tried experimenting with them?

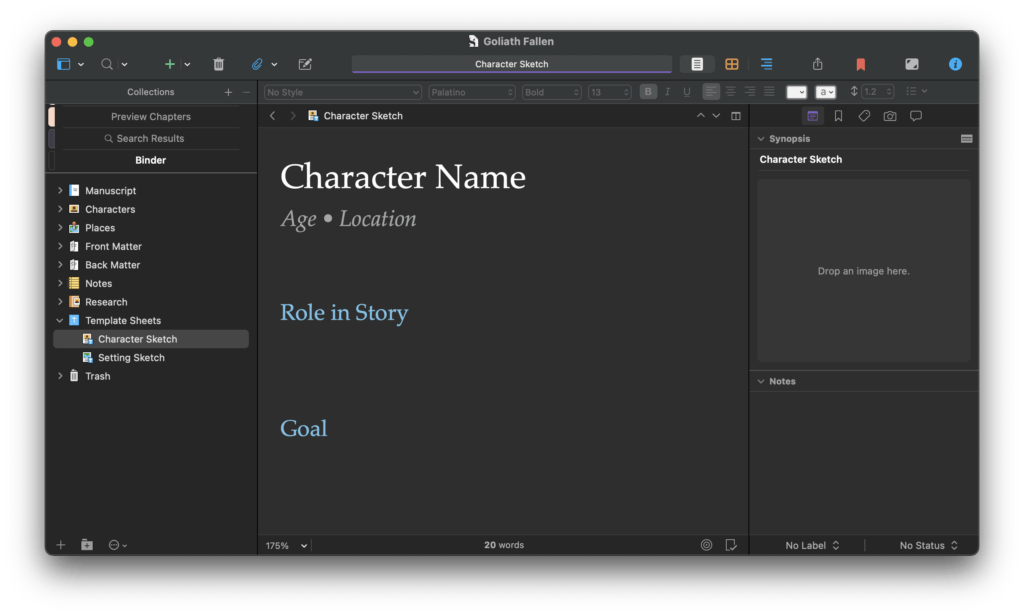

Get Two Books for Free

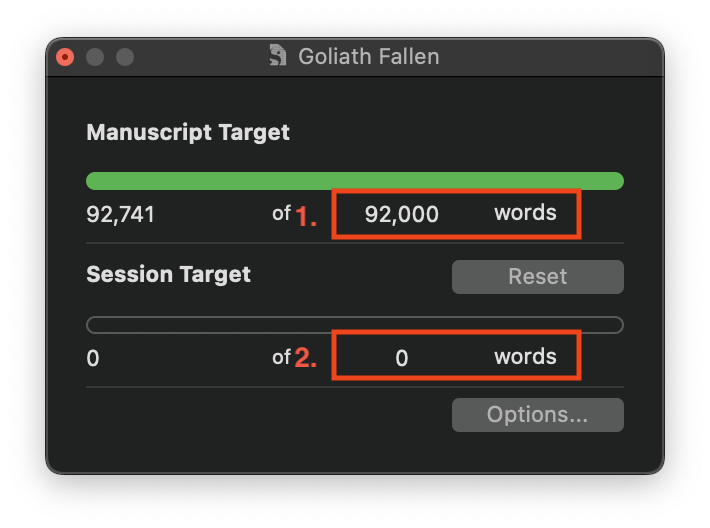

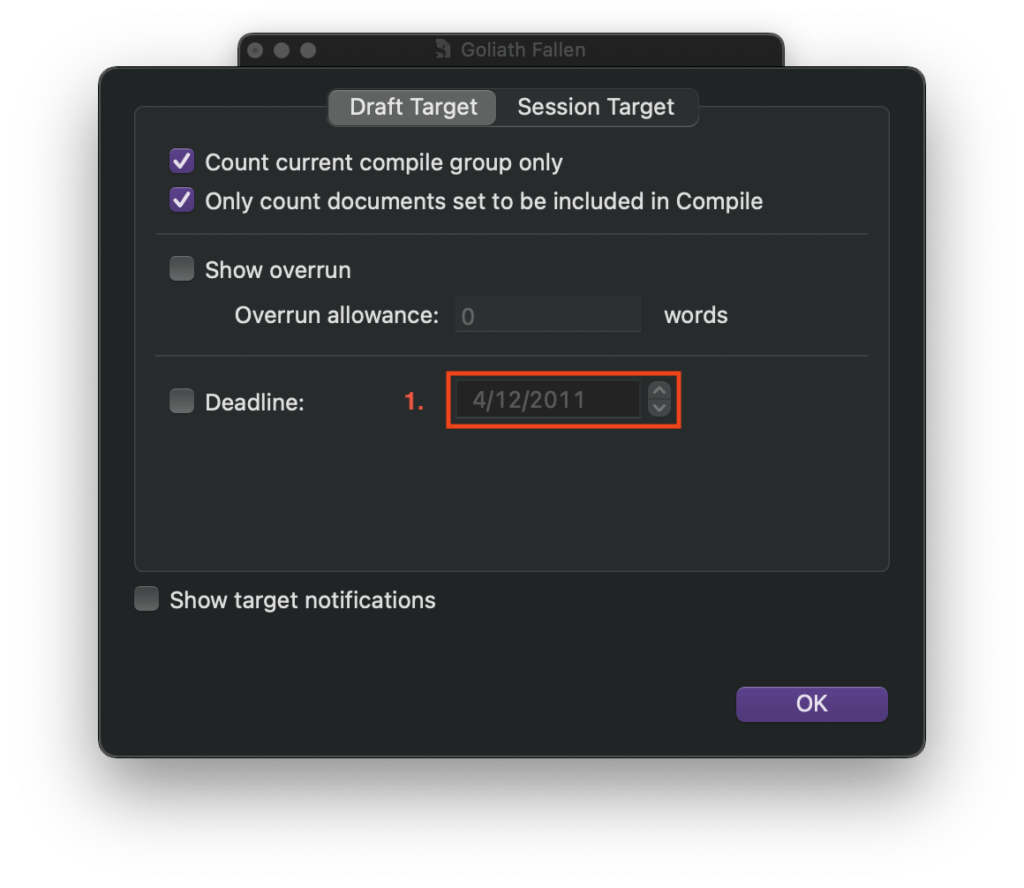

Get a preview of my sci-fi thriller, Goliath Fallen, by joining my exclusive mailing list for access to sales and giveaways. And don’t worry, I dislike spam as much as you do so don’t expect any from me. You can unsubscribe at any time.